Innocence and War: Searching for Europe’s Strategy in Syria

The author, Michael Benhamou, is the Executive Director of OPEWI. Formerly, he served as a Political Advisor for NATO and EU operations.

This long paper was originally published and financed by the Wilfried Martens Centre for European Studies.

Executive Summary

Since the start of anti-despotic revolutions in 2011, regional tensions in the Middle East—particularly between Saudi Arabia and Iran—have been most acute in Syria. The latter conflict now threatens the balance of its neighbours and the security of the entire Mediterranean basin. Faced with hundreds of thousands of refugees, one quarter of them coming from Syria, Europe’s interests are directly at stake. On the ground, Brussels is learning to adapt its tools to a situation it could not cope with at first. EU policymakers were faced with, and to this day remain challenged by, three key issues:

- slow EU Commission procedures and instruments, many ill adapted to fast-moving conflicts;

- the adverse effects of well-intended humanitarian and sanctions policies that turn against the Syrian population eventually; and

- the absence of a military culture and confidence in military options in Brussels, at the expense of the Syrian opposition.

That piece of criticism laid, EU diplomats and staffers achieved considerable cauterisation work: more than €4 billion were spent to help suffering communities with medical supplies, shelters and food, while EU diplomats strove to bring all sides to the negotiating table. Yet with regional powers such as Russia, Iran, Turkey and Saudi Arabia playing on opposite sides, it appears that no faction can reach a decisive victory on the ground, as Bashar al-Assad, the Islamic State and the Syrian opposition are holding on against each other. Cauterisation, the EU’s specialty, has turned out to be inadequate as a strategy.

With little leverage at this stage, and with Russia’s latest invasion complicating the scene further, the EU needs to learn from past mistakes. Moving beyond a purely humanitarian role, the EU should project its power differently in this violent context, with sharper civilian and military instruments in support of partners and countries sharing its values and interests.

Defending Schengen is not enough when addressing tensions in the Middle East. One needs to look at the source of the unrest.

Introduction

At the beginning of what was dubbed the ‘Arab Spring’ in 2011, one could hear a viewpoint circulating in the corridors of Brussels: ‘If there is one country that should start a revolution, it is Syria. But if one regime can resist the tide, it is the dictatorship of Assad.’

The Assad clan was skilled enough to turn a democratic revolution into a bloody civil war, affecting its immediate neighbours and Europe’s security: 250,000 casualties, 7.6 million internally displaced, four million refugees. Asylum-seeker requests to Europe have soared since 2011. One fifth of those refugees have come from Syria in 2015. On the security front, thousands of Europeans-turned-jihadists have been bathed in atrocious violence, and some are trying to come back home, now trained for combat and ready to commit terrorist acts. Syria’s borders have ceased to be relevant, as Islamic State (IS) fighters spread to northern and western Iraq. This is Europe’s most expensive external mission so far, with more than €4.3 billion already spent—€8.5 per EU inhabitant.

Back in 2011, European citizens reacted to the revolt with good cheer, as the cause of democracy tends to generate instinctive support. But it soon turned violent, and as the war dragged on, migration and security concerns became increasingly prevalent in the debate, providing ammunition for nationalist parties in Europe. Accustomed to dealing with authoritarian regimes, most EU leaders have demonstrated from the outset a certain versatility, hesitating between pro-democratic impulses and stability reflexes. In Washington, energy sufficiency and the strategic pivot to Asia reinforce dormant isolationist temptations and a lack of attention to the Middle East. As the nuclear deal with Iran has accelerated Iran’s regional rise, Saudi Arabia appears determined to counter Iran’s ambition to federate lands where the Shia community is dominant, after years of Sunni rule. Power dynamics have got the better of democratic principles and self-determination narratives.

Europe, and the West in general, leave the impression of being exhausted by the memories of recent interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan. Economic and social woes are plentiful. Engaging the Middle East and thinking about mid- to long-term solutions for that area bear few results, as every possible form of intervention has been tried—full-scale ground invasion in Iraq, air cover and air strikes in Libya, weapons delivery in Syria. Yet, with such geographical intimacy, the EU does not have the luxury of weariness when dealing with its southern shores. Regional and country-based strategies are much needed in the Middle East and with the active contribution of Central and Eastern European countries. Unity is essential, as the issue is more existential than any other.

Reaching back to the 1970s, this inquiry delves into the calculations that led many EU member states to today’s failure to act decisively:

- the EU’s oscillation between pro-democracy and pro-dictatorship tendencies,

- EU tools to identify and support like-minded partners, and

- the EU’s ability to leverage this support to alter decisions taken by local stakeholders.

The matter is not exact science, but one has to make up one’s mind on a simple cost–benefit ratio as to which is better: pro-active, daring stances or costly firefighter postures. If the EU and its allies give up on supporting partners that advocate for governance and inclusiveness in the Middle East, war will not be contained in the region. It will spread to an unprepared Europe.

1970s to 2011: the run-up to the Syrian revolution—a commercial affair

Converging paths: the Assad clan and Europe

Former Syrian President Hafez al-Assad’s 1970’s power grab was no mere accident. It was the ultimate move of decades of power plays in which his minority community, the Alawites, went from segregation to total control over the security apparatus. A religious group totalling barely 10% of the country was now definitely in command of the 70%–72% of Sunnis, 13% of Christians, 3% of Druzes and 1% of Ismailis (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Syria’s ethnic mix in the 1970s

Source: Data from Wikipedia, Syrian Civil War, Map of Syria’s ethno-religious composition in 1976.

In the 1920s the French colonial mandate had given Alawites increased autonomy, creating a substate, ‘l’Etat des Alaouites’, where access to education was at last allowed for the latter. Many joined the army as a means to counter the violence suffered beforehand: ‘Rich businessmen in large towns in Syria would hire 10 year old Alawi girls as maids . . . [T]he child would then enter a life of quasi-slavery.’

With those memories anchored, Alawites controlled key security institutions and Baath Party positions at the beginning of the 1970s, co-opting selected Sunni, Christian or Druze families into their authoritarian and patrimonial system. To preserve the randomness of this apparatus, Hafez al-Assad built an ingenious international set of alliances—with Iran, Lebanese factions, Russia, and later on, Gulf countries—all part of a clear, unavowed strategy: betting the stability of his country on the instability of the region. The more drama outside, the more legitimacy for oppressive control inside.

Europe entered that Machiavellian scene in 1977, with a Cooperation Agreement that reflected the sole weight Europe could punch at the time: economic and trade bargains. Syria was categorised as a ‘developing state’ in need of industrialisation plans and modernisation projects for its agriculture and science fields. Promotion of trade and custom duties were also an essential part of the deal.

A relationship was set between two newly born and growing partners, the European Economic Community on one side, whose foreign policy orientation was then solely in the hands of its member states—mostly France and the UK in the case of Syria—and Assad’s dictatorial system on the other.

Illusions lost . . . and lost again

In the decades that followed, the Syrian regime developed a certain nuisance power that it leveraged diplomatically, while the EU shifted its focus between three contrasted goals: buy Syria’s support for integrating the country into its own region, mediating tensions with Lebanon and Israel that would detach it from Iran; push for democratic and human rights reforms, at the very least for more freedom of expression and association; and liberalise Syria’s economy, opening it to EU exports.

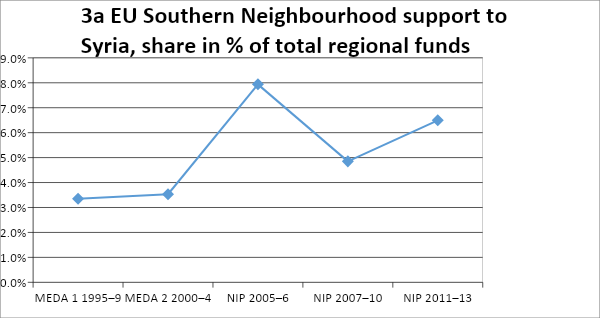

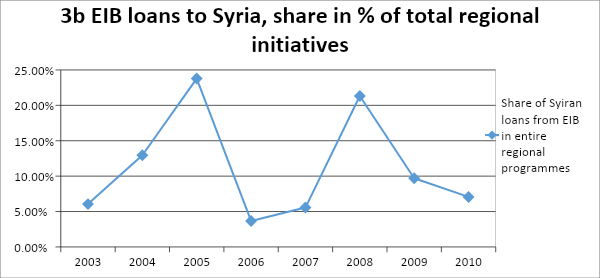

Yet, Syria set the diplomatic tempo by provoking moments of crisis and exploiting them to the benefit of the regime. Bearing in mind that projects mature at various paces, the linear upward curve for EU commitments in Figure 2 exemplifies that trend:

Figure 2 EU commitments to Syria from 1995 to 2013

Sources: Data from European Commission, Euro-Med Partnership, Regional Strategy Paper 2002–2006 & Regional Indicative Programme 2002–2004 (December 2001); Euromed, European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI), Regional Strategy Paper (2007–2013) and Regional Indicative Programme (2007–2013) for the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership (December 2006); European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI), Revised National Indicative Programme (2011–2013) of the Syrian Arab Republic (2010).

Two such moments of crisis and reconciliation are also visible in Figures 2 and 3:

- the final, isolated years of Hafez al-Assad’s rule in the 1990s, followed by the alleged reformist hope placed in Bashar, his young, Western-looking, appointed successor. French President Chirac and EU Commission President Prodi attended Hafez al-Assad’s funeral in 2000 as a symbol of their expectations of the up-and-coming Bashar al-Assad. After several years of confusion, during which some in the regime hinted at reforms, the suspicious death of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafic Hariri in February 2005 brought Damascus to new lows.

- renewed reconciliation at the end of 2007 and 2008, which peaked in 2010, and obviously collapsed when the uprising commenced in 2011.

Figure 3 Syria’s share of European funds from 1995 to 2013

Sources: Data from European Commission, Euro-Med Partnership, Regional Strategy Paper 2002–2006 & Regional Indicative Programme 2002–2004 (December 2001); Euromed, European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI), Regional Strategy Paper (2007–2013) and Regional Indicative Programme (2007–2013) for the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership (December 2006); European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI), Revised National Indicative Programme (2011–2013) of the Syrian Arab Republic (2010). European Investment Bank, 2014 FEMIP Annual Report: Transforming Opportunities into Sustainable Impact (April 2015).

Note: EIB = European Investment Bank.

France’s emotional relationship with its former colony explains in part those ups and downs. Former Presidents Jacques Chirac’s and Nicolas Sarkozy’s attempts to draw the Assads away from their alliances and to normalise Syria’s relations with Israel proved futile. Syria’s military withdrawal from Lebanon in 2005 was the exception that confirmed the rule. Europe’s lack of foreign policy cohesion was a second factor: Greece and Spain continued to engage in high-level discussions with Damascus in 2006, while Assad was considered an outcast by most EU states following accusations of the murder of former Prime Minister Hariri, in addition to continuous human rights violations.

In that environment, the Association Agreement (AA) between the EU and Syria is a lingering substory to dwell upon. Eager to implement it in 2003 when the regime’s alliances were at their lowest—relations with the US and the UK were tense after the US invasion of Iraq, as they were with Turkey—Syria was less in a hurry to sign the agreement in 2009–10 with most of its diplomatic ties restored, most notably with Qatar. European Investment Bank (EIB) loans and National Indicative Programme (NIP) funds alone failed to change the regime’s behaviour, while earlier negotiating steps in 2002–3 had put the regime back on the international stage. In 2010 the EU Parliament remarked an impression of abandonment: the new NIP provides fewer funds for the ‘support to political reforms’ box while shoring up its activities related to ‘support to economic reforms’. After all these years, building on the Syrian-European Business Centre had become Europe’s only space in which to manoeuvre.

Bashar al-Assad barricaded himself behind the ‘non-interference in internal affairs’ argument, covering up ever more visible forms of corruption through the modernisation of the economy and the installation of new telecommunication technologies, notably the Internet. The UK’s insistence on the inclusion in the AA of paragraphs related to human rights and weapons of mass destruction verification measures was overdue. Looking back, some Damascus-based diplomats have argued that ‘the regime would never have opened Syria’s economy for fear of disrupting its corruption schemes, especially at the customs entry and exit points.’ Marc Pierini adds that ‘economic policies, independence of justice, human rights or openness for civil society were not moving in the right direction anyway. Not much was left to put in the AA.’

Syria made very little concession on any of those points, preserving the stability of its patronage network at all cost, and prolonged negotiation to obtain more from other regional players. When the regime went too far, Damascus patiently waited for Europe’s public outcries and subsequent about-face, extracting more funds from the EU on the way. Facing such resistance, the EU even went one step too far in the quest for results: it resigned itself to focusing its political reform work on the efficiency of the administration’s service delivery capabilities. Those projects were hazy judgment calls: is it possible to bring a public system closer to one’s values by oiling its bureaucratic wheels pipes, or does doing so simply make a dictatorship more efficient? Given Syria’s tight control of EU moves and meetings with civil society, in addition to an absence of contact between EU embassies and Syria’s real decision-makers, a reduction of EU-led initiatives would have been preferable, rather than an increase. The European Commission should have ordered more recurrent and more transparent impact studies.

Oblivious to its failure of civil society engagement, the EU remained the main donor to Syria in the first decade of the 2000s. It silently endorsed the system in place. All along, its instruments were activated by member states whose divergent positioning and reversals failed to challenge the regime’s clan-based and highly corrupt essence.

Meditations in an emergency

‘The EU reacted swiftly and strategically to the Arab Spring’, one can read on the European Commission web portal. A review of the chronology of events, and the EU’s reactions to them, offers a more complex picture.

An incremental step in Europe’s renewed reconciliation phase with Syria was marked in 2010. The NIP 2011–13 increased by 32.3% from the preceding 2007–10 plan, abiding by Brussels’s rewarding logic: ‘Syria’s relations with EU Member States have gained momentum since 2008 . . . This has been prompted by a number of positive developments in Syria’s regional policies, such as the establishment of diplomatic relations with Lebanon, Syria’s engagement in indirect peace talks with Israel during the second half of 2008, and rapprochement with Arab neighbours such as Iraq and Saudi Arabia.’ Commenting on minor social and institutional evolutions, the document eventually recognises that ‘other aspects of the domestic political situation have remained unchanged.’ Right after this confession, the next sentence exemplifies the EU’s core logic: ‘[I]nternal stability has been maintained despite regional instability and the presence of a large population of Iraqi refugees.’

The 9/11 attacks and the violent aftermath of the 2003 Iraq war motivated member states to accelerate this cooperation. Syria’s ‘security diplomacy’ was in full swing as Syria’s minister of interior toured Europe to provide sensitive counterterrorist intelligence. The statement of Syria’s minister in charge of economic affairs also played a role in this enthusiasm: ‘[W]e need $50 billion to rehabilitate our port, airport, electric and hydraulic infrastructures.’ With the support of the EIB, dozens of projects were already under development or in negotiation when the pro-democracy uprisings began in Tunisia in December 2010.

Responsible for Enlargement and Neighbourhood policies at the time, Commissioner Füle’s attitude was particularly ambivalent in those first decisive weeks. Signing a statement on 17 January 2011 asking for ‘a peaceful democratic transition’ in Tunisia that has now ‘reached a point of no return’, the Commissioner travelled to Damascus a few days later on 25 January to insist that ‘Syria and the EU share an interest to foster a stable, peaceful and prosperous Middle East.’

Füle’s mea culpa intervened quickly after—at the end of February 2011—but the 2011 revolutionary boat took off, with the sense that Europe was caught off guard. By March 2011, European institutions were slowly catching up with events in Syria. As protests started in the south of Syria, in Deraa, on 6 March, the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs, Catherine Ashton, called upon Syrian authorities to reconsider all cases of prisoners of conscience, a plea for the teenagers arrested by the regime earlier that month and derived from previous calls for those jailed beforehand. Afterwards, Europe’s diplomacy proved extremely reactive to events and incremental in its reformist vocabulary: ‘political dialogue and genuine reforms’ (22 March), ‘protests calling for reforms and democracy’ (9 April), ‘peaceful transition to democracy’ (23 May). Programmes under the ENPI were suspended on 25 May, while EIB loan agreements were put on hold a few months later, in November 2011.

Europe’s reaction to the Syrian revolution was neither swift nor strategic. Bashar al-Assad did not have the authority to take the reformist olive branch the EU offered, and both sides were eventually inebriated by the habits of stabilisation and commercial opportunities. Europe’s programmes—worth €450 million between 1995 and 2010, as seen in Figure 2—were tightly controlled and reached a very limited crowd. Its early reflexes were again based on a wrong assessment of Assad’s regime, where violence always trumps compromise. Syrian civil society movements were kept at a distance. If those timid attempts at engagement obviously did not turn the EU into a role model when the revolution arose, help was direly needed to face a regime that escalated tensions with rare brutality.

2011–13: the failure to support Syrian moderates

The revolution’s early days

Opinions differ on the nature of the uprising’s early 2011 moments. Some analysts argue that Islamic movements were already involved as of March 2011 to use Deraa’s repression to their advantage. Others respond that the presence of Saudi Arabia-backed supporters and of the Muslim Brotherhood was barely marginal in 2011; Syrians wanted an end of Bashar’s rule, and their call for democracy was sincere. One element is uncontested: young Syrians were increasingly able to bypass the government’s Internet firewalls, via web proxies, and read about less dictatorial forms of government. The regime’s ineptness was on display.

Areas conquered by the moderate opposition in the north and south were represented by two movements, one engaging in battles within Syria—the Free Syrian Army (FSA)—created in July 2011 and officially reporting to the second group, a civilian one and Istanbul-based—the Syrian National Council (SNC)—formed in August 2011. Another dynamic operated as well at the subnational level, without formal structures at first: charity networks mostly oriented towards health care support.

The SNC strove to integrate those two processes, subnational and external, and went on to set up elected municipalities and governorates in Idlib, Aleppo and Raqqa. Hundreds of staffers surrounded those representatives, ‘neophytes in politics yet suddenly confronted with people’s requests, mostly the reestablishment of public services’. Many were selected for their professional competences and their political weight. In parallel, Kurds in the northeast signed a non-aggression pact with Damascus and filled the vacuum left by the departure of Assad forces. By the end of 2012, the Partiya Yekitiya Demokrat (PYD) and its armed wing, the Yekineyen Parastina Gel (YPG) oversaw military and police forces, ran tribunals and prisons, and distributed humanitarian aid.

Until 2013, many analysts believed the Assad regime would be quickly defeated by opposition movements, though Western-backed efforts to arm rebels through the Military Operations Command were largely overtaken by stronger support for Assad by Iran and Russia and by Gulf States, and by Saudi Arabia for extremist Sunni groups. Towns were lost to the opposition, but the regime continued to impose its military pace on the course of events. A poorly trained and financed opposition could hardly control and administer territories that were being blindly bombed by Assad’s tightly organised security apparatus and surrounded by a growing jihadist threat.

Brussels’s institutional response

The birth of the EU’s newly created diplomatic service could have been more fortunate. Launched on 1 January 2011, the European External Action Service (EEAS) was to oversee and coordinate Europe’s foreign policy instruments, formerly led by the EU Commission, at the beginning of the Middle East’s revolts—two weeks after the start of the revolution in Tunisia in December 2010, three weeks before the protests began in Egypt at the end of January 2011. Its first Director for the Middle East and Southern Neighbourhood was appointed on 21 December 2010 while the EEAS Brussels offices were still being set up.

EEAS diplomats and Commission colleagues had many tools at their disposal to deal with the challenges ahead: 15 years of direct, programme-based experience with Damascus; an expert study performed by the Commission to map Syrian civil society in 2007, despite the regime’s blocking interference; and obviously, the support of EU member states with deeper historical roots and networks in the country. Brussels became a programme management hub, though its newly arrived EEAS diplomats had little experience in the latter.

Figure 4 The EU’s horizontal, star-shaped crisis response for Syria

Source: Data from the author’s own visualisation of institutions, based on institutional interactions observed since 2011.

Note:

Crisis Platform = the EU’s main coordination hub for crisis management.

DCI = Development Cooperation Instrument;

DEVCO = DG Development and Cooperation;

EBRD = European Bank for Reconstruction and Development;

ECHO = DG Humanitarian and Civil Protection;

EEAS = European External Action Service (Europe’s diplomatic service);

EIB = European Investment Bank;

EIDHR = European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights.

ENI = European Neighbourhood Instrument;

FPI = Service for Foreign Policy Instruments;

HIP = Humanitarian Implementation Plan

IcSP = Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace (formerly called Instrument for Stability (IfS));

IPA = Instrument for Pre-Accession.

Madad Fund = EU Trust Fund that allows the EU and its member states to pool resources;

NEAR = DG Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations;

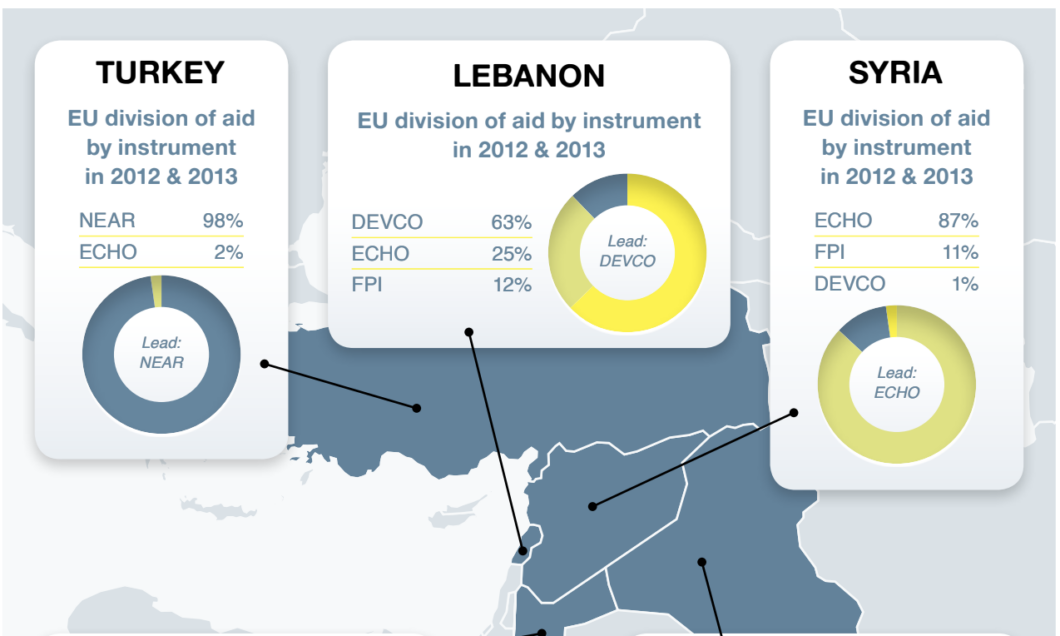

Brussels had faced dozens of conflicts in its neighbourhood before, but how would its post-Lisbon institutions behave in what is now referred as the ‘EU’s largest crisis management situation ever encountered’? Using almost exclusively humanitarian and development tools, the EU’s traditional horizontal decision-making process framed the response in Syria (Figure 4). Coordination is, unsurprisingly, vital when many departments get involved, a difficult undertaking in the Syrian context, as countries falling in varying EU boxes were impacted. Three Directorate Generals (DGs)—DG Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations (NEAR), DG Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection (ECHO) and DG Development and Cooperation (DEVCO)—were spread over five countries: Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and Syria. ‘It challenged structures that were not meant for this’, an EU Commission official confessed. The following map shows the involvement of a disparate array of EU actors.

Figure 5 Mapping the division of efforts among EU institutions

Sources: Data from European Commission, DG for Development and Cooperation, Annual Report 2014 on the European Union’s Development and External Assistance Policies and Their Implementation in 2013, COM (2014) 501 final (1 August 2014) and Staff Working Document (13 August 2014); European Commission, DG for Development and Cooperation, Annual Report 2013 on the European Union’s Development and External Assistance Policies and Their Implementation in 2012 (2013).

Note:

DCI = Development Cooperation Instrument;

DEVCO = DG Development and Cooperation;

ECHO = DG Humanitarian and Civil Protection;

EIDHR = European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights;

ENPI = European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument;

FPI = Service for Foreign Policy Instruments;

IfS = Instrument for Stability (now called Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace);

IPA = Instrument for Pre-Accession;

NEAR = DG Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations instruments;

NSI = Nuclear Safety Instrument.

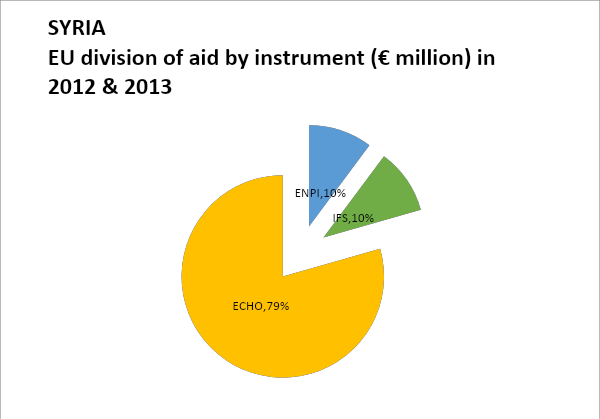

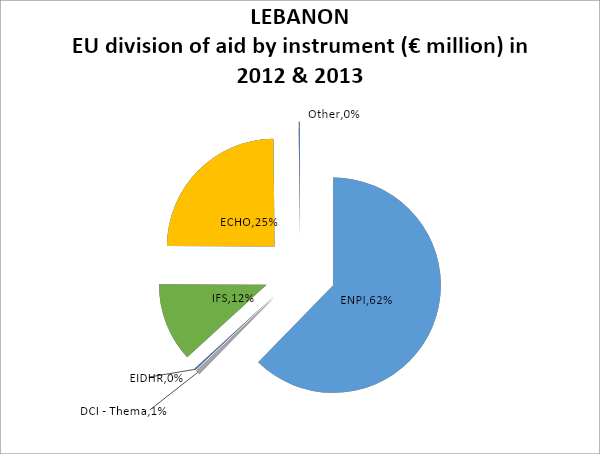

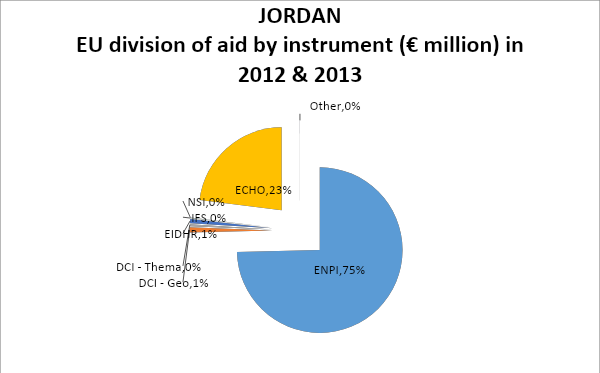

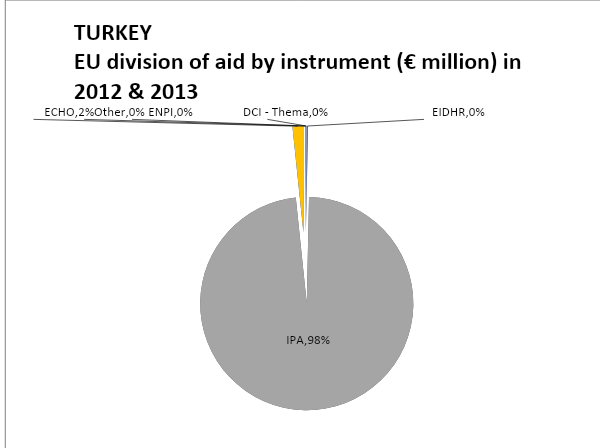

In addition to the Geneva negotiations, the EEAS’s key task was to watch over the coherence of the EU’s efforts. The EEAS Crisis Platform sessions have occurred frequently since 2011, while bureaucratic lines have shifted elsewhere. At the beginning of 2015 budget lines were reoriented in favour of DG Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations (NEAR), whose role was reinforced through the European Neighbourhood Instrument 2014–20 spending programmes and the creation of an EU Regional Trust Fund in Response to the Crisis in Syria, the Madad Fund. EU assistance to Lebanon and Jordan clearly points to a ‘NEAR lead’ through the European Neighbourhood Initiative. In Turkey, DG NEAR plays a decisive implementing role as well, using another tool, the Instrument for Pre-Accession (IPA). Its original purpose, though—support to reforms before a potential entry in the EU—was diverted to handle Syria’s refugee situation.

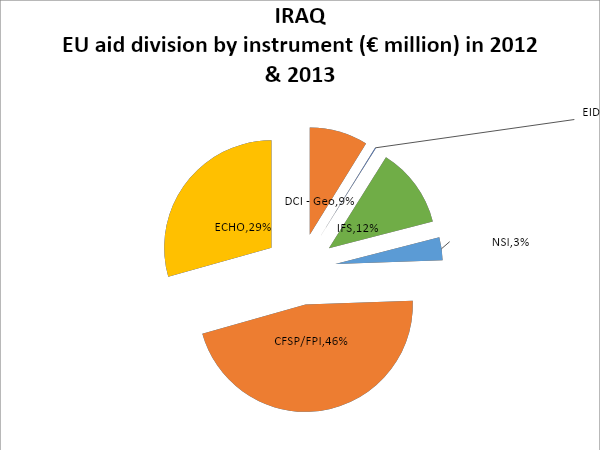

On the other hand, DG Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection (ECHO) has been the main aid provider within Syria since 2011, while a civilian Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) crisis management mission, EUJUST LEX Iraq, and DG Development and Cooperation (DEVCO) have led EU efforts in Iraq. Two DEVCO instruments were used extensively there, the European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights, in support of human rights defenders or victims of abuse, and the Development Cooperation Instrument, a large envelope that covers governance, poverty eradication and rule of law programmes.

On the ground, the EU is proving its ability to pool resources from individual member states. EU delegations in Amman, Baghdad and Beirut carry a growing political weight alongside key EU member states’ embassies. The EU delegation in Damascus even welcomed diplomats from closed EU embassies before its own departure at the end of 2012. EU visits to Damascus continue to be held from Beirut on a monthly basis. The EU office in the south of Turkey, in Gaziantep, is another case in point: diplomats and aid workers from France, Germany and Denmark develop projects daily there, assisted by local staff. Of note, the UK follows a separate path, channelling its assistance through its Department for International Development. As Syrian civil society grew frustrated with receiving food packages, the EU’s help shifted more and more towards ‘resilience and recovery activities’. Offering traineeships for entrepreneurs and classes on civil defence, and focusing more on education and livelihoods are now central in the EU’s approach.

Listing those budget lines, and their large financial dimensions, one realises that the Syrian war profoundly disturbed the EU’s crisis responses in three ways:

- The 2007 Lisbon Treaty’s attempt to detach foreign policy from the EU Commission’s grasp could not be implemented in the face of events. The Commission’s coordinating and budgetary influence paradoxically soared when the Syrian conflict began. Commission experts from conflicting EU administrations were therefore immersed in a highly political scene, while Europe’s diplomatic service, the EEAS, was still striving for visibility and influence. The non-success of the Madad Trust Fund for Syria, whose pooled funds are very low, is a case in point: launched by DEVCO without coordination with the EEAS, it was met with frigidity by EU member states, which had not been engaged in the initial planning process.

- Doctrines, manuals and habits continue to be shaped by humanitarian and development reflexes: data solutions, intelligence gathering, mapping techniques, all more frequently used by militaries, were insufficiently developed. Security and military experts remain scarce in EU delegations. EU staff and budgets are not truly fit for warfare scenarios: ‘[M]any of our instruments were designed for recovery situations. But in Syria, there is no recovery, only increasing destruction.’

- EU institutions never involved their own military instruments to solve a military situation. The reasons for disregarding the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) are clear: lack of military resources due to member states’ refusal to comply with the 2% minimum for military spending, refusal by the EU to cover military costs and burdensome procedures, most notably due to the absence of an EU military headquarters. Launching a CSDP mission in such a volatile neighbourhood could take six to nine months, while the operationalising of EU civilian instruments has been hastened since 2011 to cope with the Syrian war.

In search of lost time

Opportunities were missed in those early volatile years. Is it fair to claim that a more moderate side could have prevailed over Syria or parts of it? What do we mean by seizing opportunities?

The fall of towns in the east, most notably Raqqa in March 2013, to more moderate factions within the FSA, led many to believe that governance opportunities would finally have a chance to be realised. Civil society groups quickly organised themselves: doctors, professors, journalists. Citizens were elected. A city council was formed. Almost immediately, as of May 2013, IS started to terrorise the population, kidnapping targeted individuals and mapping the town’s hubs and centres of gravity before taking over definitively in August of that year. In October 2013, two inhabitants were executed for speaking openly against IS in a public meeting, systemising fear over the city. Outside support to the local council was limited during those decisive months.

The West’s choice not to provide significant operational support to local partners had direct consequences. The FSA was never able to patrol in the Kurdish town of Kobane early on, and the opposition in Aleppo has always been divided between its numerous contrasting supporters, none decisive. US President Barack Obama explained this choice, in the last hurdles of the Iran nuclear deal:

This idea that we could provide some light arms or even more sophisticated arms to what was essentially an opposition made up of former doctors, farmers, pharmacists and so forth, and that they were going to be able to battle not only a well-armed state but also a well-armed state backed by Russia, backed by Iran, a battle-hardened Hezbollah, that was never in the cards.

Without substantial military support and the imposition of a no-fly zone, or at least air support as is implemented now for a pocket in the north of Syria, local governance was close to impossible.

Given this tactical and geopolitical context, the EU’s operating rules and regulations were markedly put to the test. Identifying a project, preparing the call for proposals and synthesising the feedback of DGs could take 18 months before an initial disbursement was made. But, progress has been made since. In February 2015 the ‘regional strategy for Syria and Iraq’ insisted on the necessity to ‘scale up preparedness and rapid response capacities’. Faster instruments are increasingly pervasive in the EU’s modus operandi:

- The Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace is entrusted with more funds than the Instrument for Stability (IfS), which it replaced in 2014;

- The recent creation of the Rapid Reaction Mechanism (RRM) has also fulfilled that reactivity wish: ‘[T]hese RRM actions are financially limited to a certain amount but they can be actioned in 48 hours with few signatures needed and for non-humanitarian projects.’

Groups such as IS will always be faster than external organisations with few eyes on the ground, but at least the gap is substantially bridged if a political decision is reached to support a partner.

The Syrian crisis called into question the EU’s operational methods in two other instances. Providing funds in a timely and predictable way is essential to support groups whose legitimacy rests mainly on that largesse. Stock arrangements were one of the lessons learned of this conflict. Aid and development policies were very often debated as well: ‘[S]hould we continue to sign large cheques to the UN or operate via multiple partners on a case by case basis?’ The latter approach, that is, a more granular support to civil society, is best embodied today by the European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights and the European Endowment for Democracy.

If these efforts deserve full attention, they remain financially marginal in the EU landscape, compared to DG ECHO or NEAR. The bulk of budgets dedicated to Syria remains tied to heavy bureaucratic regulations where indicators, monitoring and results-based criteria rule decision-making processes. Officials met on the ground do not just blame circumstances but also point to missed opportunities by the EU due mostly to lengthy procedures. Very few EU institutions would shift substantial amounts of funds to a half-trusted partner in need of assistance if it suddenly took control of a town or a region. Brussels is not the type that does a U-turn to back a horse whose governance claims might not be so genuine. Accountability needs clash here with risk taking. Unwilling to reach such strategic depth, Brussels cautiously plays on a less impactful comparative advantage: deep-rooted social fixes.

2013–15: throwing compassion at chaos

Assad’s resilience in an explosive regional war

The year 2013 proved disastrous for the Syrian opposition. Having failed to coalesce all movements around its name, the SNC merged with the National Coalition for Syrian Revolution and Opposition Forces in November 2012. Composed of a growing number of groups viewing sharia as the unique source of laws and unwilling to treat non-Muslims as equals, the opposition found its sole consensus in the departure of Assad. Barack Obama’s refusal to strike Assad’s forces after Syria had crossed a US-set ‘red line’ on the use of chemical weapons in August 2013 demoralised moderates further. Fruitless diplomatic negotiations between Assad and the opposition (Geneva I and II) accelerated a sense of despair. The former continued to betray his word on ceasefire agreements. Cheap barrel bombs were then used, killing thousands of civilians.

Sectarian Islamist movements emerged decisively from that chaos. Al-Qaeda’s affiliate, al-Nusra, announced its formation in January 2012 but was soon challenged by an even more radical group, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). Later called IS, the group patiently infiltrated towns in northern Syria in the spring of 2013, gathering information and piling weapons in caches. Led by former secular Iraqi officers and composed notably of foreign fighters, IS professes a radical view of Islamic texts. The group pursued its offensive in Iraq, taking over Mosul in June 2014 and Ramadi in May 2015, and threatening Baghdad ever since. Those successes emboldened the IS leadership to revive the Islamic Caliphate as of June 2014. Assad clearly helped IS, releasing jihadist prisoners and aiming random fire at cities or neighbourhoods held by the more moderate opposition, which is now tactically annihilated.

Risk averse and out-manoeuvred, Western leaders have lost any control. What is left of Syria’s moderate middle class is now being bombed by Russian fighter jets and helicopters. Assad can now regain the western territory lost to the Islamist opposition in 2015. IS is increasing its hold of the eastern half of the country and threatens Aleppo, Syria’s second major city. Syria’s Kurds are firmly anchored in the northeast, worried by IS incursions and Turkey’s active destabilisation.

At the end of 2015, the dynamics are quite clear:

- Assad, Iran and Hezbollah are cleaning up territories held along the coast, in the southern areas, the Qalamoun, and in the capital, with the help of newly arrived Russian fighter jets and soldiers.

- Saudi Arabia is already reacting by providing more destructive weapons to the Islamist opposition, most notably to the al-Qaeda-affiliated al-Nusra Front. Turkey and the Gulf States are also supporting those same factions in the north, notably those that hold half of Aleppo.

- Western countries are clearly reducing their support to opposition groups in the north and south, while Western-led Coalition airstrikes continue against IS, notably in support of Kurdish held areas.

- IS is slowly expanding in the north, battling the Kurds and Islamist rivals.

Overall, there appears to be little motivation for a peace process.

Beware of pity

As the war’s intensity increased, Europe’s influence remained voluntarily discreet. Most of the EU’s aid is spent through multinational trust funds. When mentioned in Jordan, Lebanon or Turkey, the EU is often described as ‘the organisation that focuses on capacity building and humanitarian causes’. In newspapers, Twitter feeds or think tank debates, Europe’s efforts are almost never mentioned. And yet, the EU’s reaction to the Syrian conflict was the largest of its history. It is the most sizable aid donor to Syria.

Europe responded to the crisis in two main ways, by providing care for the victims of the conflict and by sanctioning the leaders of the Syrian regime accused of war crimes. That sanction regime did not bear the expected fruits, as rumours had predicted that the regime would quickly run out of money before summer 2013. In the meantime, millions of refugees have poured into countries that do not have the institutional capacity to face the situation (Lebanon, Iraq) or that need solidarity to support their administration (Turkey, Jordan). Some of them are now coming to Europe as, after four years of conflict, they have lost the hope of returning to their own country.

Supporting the UN, member state agencies or local non-governmental organisations, the EU sends its help through various channels and for numerous emergencies, setting up camps where 20% of refugees truly reside, arranging classrooms so as not to disrupt children’s education, and providing food packages and shelters. In total, €4.3 billion have been spent since 2011 on Syria and affected countries in the neighbourhood, mostly Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey and Iraq. Another billion euros have been budgeted for 2015 and 2016—a victory for the EEAS, which had to argue Syria’s case, as tensions in Ukraine and Africa also require the attention of Brussels’s decision-makers.

Brussels decided on a double 50/50 rule, that is, 50% within Syria, 50% for neighbours; 50% of the aid for Syria is dubbed ‘cross-border’—passing through Turkish and Jordanian borders directly—while another 50% is defined as ‘cross-line’—passing through Damascus and therefore controlled and monitored by Assad’s regime. Difficult compromises had to be struck so that help could be delivered with safety guarantees. Accustomed to those missions, the EU was able to quickly scale up its aid based on one core humanitarian principle, ‘do no harm’, which means targeting the right audience while limiting adverse effects. Still, EU policies in Syria have had three key unforeseen consequences:

- Care and its effects. Aid to Syria has distorted food prices, particularly wheat, a damaging adverse effect, as half of the Syrian population are rural dwellers. Paradoxically, and because of the conflict itself, inflation ran high until September 2014, impacting once more Syrians’ purchasing power.

- Neutrality and its contradictions. Aid is envisioned in the EU as ‘neutral, impartial and independent; it does not imply political engagement and cannot be considered as a crisis management tool.’ The brutality and complexity of the Syrian conflict stretched those principles, as portions of that aid benefitted villages held by IS or by the Assad regime. So far, the EU has resisted Assad’s blackmailing tactic to break the 50/50 rule: Damascus pushes for a reduction of cross-border aid in opposition-held areas, passing through Jordan and Turkey, in exchange for more access for EU staff and programmes within the regime-controlled parts of Syria. Furthermore, sustainable development activities, prone to give enhanced legitimacy to local governance actors, target mainly EU partners. That said, humanitarian help continues to reach all individuals in need, thereby supporting groups that EU member states and the US oppose militarily.

- Sanctions and the war economy. The EU quickly crafted sanctions against the Syrian government, specifically aimed at those involved in the activities of repression, and banned the export of certain goods (luxury items, metals, gold, oil and gas). This sanction regime failed to destabilise Damascus and created a war economy that benefits some members of the Assad clan. Worse, direct support to like-minded NGOs is impeded by the embargo on oil and construction material, as the Syrian population did not cope with the bans as deftly as criminal networks tied to the regime. The consensus on sanctions remains strong, though, among EU member states, as marginalising the Assad regime is prioritised.

The aid poured into the Syrian conflict by the EU was essential to slow down further spillovers, but indirectly served the ongoing escalation. The EU’s clumsy political indecision increased the isolation of the opposition fighting inside the country while providing a cushion for its adversaries, whether IS or Bashar al-Assad. Principles hailed by Syrian revolutionaries at the beginning of the revolution—democracy, rule of law—now generate instantaneous reactions of anger from surviving activists. Some have joined more radical movements since. They wanted to fight and not beg.

Today’s Middle East: reform or war

‘The new borders in the region are those drawn in blood’, warns Massoud Barzani, President of the Iraqi Kurdistan Region. Four years since the start of the Arab Spring, Saudi Arabia and Iran are engaged in a series of long-distance duels—in Lebanon, Yemen, Iraq, the Occupied Palestinian Territories, Syria—deepening the Shia/Sunni divide. The Middle East is fractionalising into portions of land held by tribes, communities and criminal networks that control towns with hoards of vast underground wealth. The partitioning of Libya exemplifies the latter: roads held by regional smugglers and towns where oil and gas is extracted have become fault lines. Minorities are each time among the first casualties: Christians represented 25% of the population in the Middle East at the beginning of the twentieth century. They now account for 5%. Europe’s security is at stake as well as its economy: there is a growing danger of maritime transportation in the Mediterranean Sea becoming more expensive for companies, as violence persists and insurance prices rise. EU humanitarian workers now anticipate millions of additional displaced persons, as 30% of the Middle East is now inaccessible due to safety concerns.

Europe does not state clear goals for its Southern Neighbourhood. The EU’s positioning in Iraq is highly symbolic of the continent’s hesitations: ‘EU support to Kurdish armed resistance to IS must be accompanied by strong assurances to the states of the region of continued EU respect for their territorial integrity’; further, regarding Syria this time: ‘the EU will continue its efforts, bearing in mind that the collapse of State institutions in Syria must be avoided’. Europe is not ready to break any Westphalian taboos, as Brussels knows what awaits if post–First World War borders are fundamentally put into question: more civil war, more terrorism, more refugees.

Along with several EU leaders, the former EEAS chief, Catherine Ashton, offered her full attention and weight to Tunisia’s positive democratic example and sided with Mohamed Morsi, elected President of Egypt in June 2012 and also a member of the Muslim Brotherhood. Close to 20 visits to Cairo were arranged. His demise in July 2013 and the takeover by the Egyptian Army exposed the futility of EU and US policies once again. Beyond the rejection expressed by a popular movement, the EU and its allies were unable to alter the governance methods of the Muslim Brotherhood and effectively oppose Saudi Arabia’s counter-revolutionary ploys.

Those discussions also reveal the need for a stronger military component in the EU’s global posture. With a CFSP at barely 2.3% of the total 2014–20 EU budget, and declining military expenditures on the continent, the EU is not dimensioned to play a military role in any Middle Eastern conflict, whether one considers offensive actions or lower-intensity missions such as peace enforcement or post-conflict stabilisation. Discussions in 2015 over a potential intervention on Libya’s coast showed that any significant operation targeting migrant smugglers would involve ground troops in Libya’s key harbours, a complex, lethal scenario requiring coordination and intelligence capabilities the EU does not possess. Deprived of military headquarters, EU Battlegroups, theoretically operational since 2007, have so far never been deployed on the field, as member states keep arguing over financing and legal technicalities. NATO remains the sole organisation with the confidence and experience to carry out such tasks.

‘Train and equip’ discussions have been elevated on the EU agenda, as direct military intervention has lost its allure. The provision of military equipment and training to selected partners is already underway in two African countries via DEVCO and Service for Foreign Policy instruments. The system’s fluidity is questionable, though, as EU policymakers need considerable bureaucratic creativity once more to bypass legal and financial hurdles. Confidence in the process is too low to be used in today’s Middle East, particularly in Syria, where risks of misuse are too high for a newborn EU endeavour that needs practice. Barring a significant political push, full ‘operationability’ for EU capacity-building programmes is only possible in five to six years, tagging on newly negotiated lines to the EU’s 2020 budget.

With a defensive foreign policy discourse now hostage to terrorism and migration concerns, EU leaders assuage themselves with the hope of becoming mediators in the Middle East, ‘once the situation settles down’. In Syria, Brussels values its neutrality posture, reminding all at Geneva discussions and beyond that it remains the only organisation that ‘did not bruise anyone’. A problematic question then emerges: who will be left in the end to engage?

Conclusion

Europe’s weight with Syria and its neighbours changed dramatically when the revolutions began: marginalised since the 1970s by member states—managing projects with little civil society impact and negotiating trade agreements—the EU is now coordinating vast sums of money on its own terms, in the neighbourhood’s most lethal crisis.

That said, Europe’s institutions are not political enough to carry such tasks on their own. The violent nature of the Syrian conflict brings us back to the reality of the EU’s cultural bias—civilian, not military. Who would send humanitarian workers to Military Operation Command’s meetings, where guns are distributed and military tactics are discussed? How would risk-averse institutions react if Western allies were to suddenly request an answer within two to three hours maximum on the opportunity to supply weapons to semi-reliable local partners when their village falls to the IS?

The EU has rightly left those tactical judgement calls to member states so far, but this also contradicts Europe’s growing weight and common interests on migration and anti-terrorism. The EU’s Comprehensive Approach cocktail needs to be stepped up and aimed at preventing conflicts. The IS and other radicalised groups are moving fast, under the radar, making full use of local networks to strike and terrorise. This calls for local, case-by-case and civil–military responses where Europe makes it clear that it has not given up on civil society and on governance issues.

A war on ideals is being waged in which Europe’s references are no longer mainstream. Radical Islamist groups are increasingly taking hold of urbanised youths’ imaginations as corrupted regimes refuse to change and adapt. An idealistic foreign policy does not mean that democracy should prevail everywhere; it could mean that Europe expects more reforms, and an end of the support to terrorist groups, in exchange for cooperation.

Out of its element and out of resources, Europe cannot simply pursue a blind defensive strategy in which its taxpayers foot the bill for the region’s woes. Moderate partners are slowly crumbling. A more flexible and determined model is needed to demonstrate support and defend Europe’s interests and values against their enemies.

Policy Recommendations

Besides high-level diplomatic actions, not discussed below, there is room for lower level initiatives that could make a difference on the ground:

- Launch an impact study on the sanctions regime decided on Syrian goods. Recalibration is needed, as the population and local partners are dealt more blows than the Assad regime, which has learned to bypass sanctions.

- Increase the amount of aid delivered to Syrian refugees in Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey. The ongoing refugee crisis is also due to a decrease of aid to the area. Close to 40% of the relief efforts requested by the United Nations have been provided, that is, $2.7 billion were funded out of $7.4 billion requested to cover needs. Lobbying and follow-up of countries’ contributions at the next donor conference in Oslo will be essential.

- Despite Russia’s increased support of Assad, reinforce Europe’s help to what remains of opposition groups in the north and south by establishing safe havens and providing weapons and ammunitions. EU member states should not make the mistake of looking towards Russia for any resolution of this conflict. The US and Sunni Arab states will need to be engaged to revive a more moderate Syrian opposition. The battle for a relevant opposition is not lost, despite the Assad regime’s efficient propaganda.

- Support governance reform efforts and decentralisation models. Syrians know what they would lose with talk about partition, and most would accept a decentralised Syria with autonomous local police units to guarantee the safety of all communities. The UN’s mediation and expertise would be essential. The departure of Bashar al-Assad and his entourage is the only non-negotiable condition heard in discussions with Syrians.

- Adapt EU instruments—namely, the Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace and DEVCO’s European Development Fund—to grant them the right to provide military equipment and training. In the medium term, the EU Parliament should push for the creation of a new Train and Equip instrument dealing with capacity building. That international network development philosophy is already underway for civil protection activities.

- Spend more on security and defence to complement EU civilian instruments. Given the security climate, EU member states are mistaken in not respecting the 2% GDP target on defence—Europe averages 1.2%, far less than rising military needs. The EU’s industrial cooperation on defence products is shrinking as well as military research and technology/development budgets (-25% over the past five years). On the Brussels front, the EU’s institutions are also wrong in dedicating only 4% of its 2014–20 external budget to security matters. Those anti-military trends account for the CSDP’s grand absence in the Syrian crisis.

Europe needs to send a message of deterrence and of solidarity: solidarity for the victims of conflicts and better support for those that still want a better Middle East. There remain in Syria, as in all embattled countries in the Middle East, majorities seeking a future without ideologies, without violence. Can Europe empower them?

Bibliography

Backzo, A., Dorronsoro, G. and Quesnay, A., ‘Syrie: où en est l’insurrection?’, Annuaire Français de Relations Internationales, XV, 2014, accessed at http://bit.ly/1N2XGA9 on 8 July 2015.

Butter, D., Syria’s Economy, Picking up the Pieces (London: Chatham House, the Royal Institute of International Affairs, June 2015), accessed at http://bit.ly/1R96xBd on 13 October 2015.

Casagrande, G. ‘Russian Airstrikes in Syria: September 30, 2015–October 5, 2015’, Institute for the Study of War, accessed at http://bit.ly/1OXAAy8 on 13 October 2015.

Charbel, G., ‘Barzani: The Region’s New Borders Will Be Drawn in Blood’, Al Monitor, 15 February 2015, accessed at http://bit.ly/1L3hMcT on 4 July 2015.

Chesnot, C. and Malbrunot, G., Les chemins de Damas: le dossier noir de la relation Franco-Syrienne (Paris: Robert Laffont, 2014).

Council Regulation (EEC) no. 2216/78 concerning the conclusion of the Cooperation Agreement between the European Economic Community and the Syrian Arab Republic, OJ L269 (27 September 1978), accessed at http://bit.ly/1VIvuor on 26 August 2015.

Euromed, European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI), Regional Strategy Paper (2007–2013) and Regional Indicative Programme (2007–2013) for the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership (December 2006), accessed at http://bit.ly/1RxPlGq on 7 May 2015.

European Commission, Capacity Building in Support of Security and Development—Enabling Partners to Prevent and Manage Crises, Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council (2015) 17 final (28 April 2015).

European Commission, DG European Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations, ‘EU Regional Trust Fund in Response to the Syrian Crisis, the ‘‘Madad Fund”’, Q&A with additional information for partners (2015), accessed at http://bit.ly/1SG0hmX on 26 August 2015.

European Commission, DG European Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations, Southern Neighbourhood (updated 25 April 2015), accessed at http://bit.ly/1f7V6gK on 26 August 2015.

European Commission, DG for Development and Cooperation, Annual Report 2013 on the European Union’s Development and External Assistance Policies and Their Implementation in 2012 (1 August 2013), accessed at http://bit.ly/1MfQSPw (2013) on 15 November 2015.

European Commission, DG for Development and Cooperation, Annual Report 2014 on the European Union’s Development and External Assistance Policies and Their Implementation in 2013, COM (2014) 501 final (1 August 2014), and Staff Working Document SWD(2014) 258 final (13 August 2014), accessed at http://bit.ly/1hujYzq on 14 September 2015.

European Commission, DG for Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection, ‘Syria Crisis’, ECHO Factsheet (November 2015), accessed at http://bit.ly/1ftTuMD on 5 November 2015.

European Commission, Elements for an EU Regional Strategy for Syria and Iraq as Well as the Da’esh Threat, Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council (2015) 2 final (6 February 2015).

European Commission, Euro-Med Partnership, Regional Strategy Paper 2002–2006 & Regional Indicative Programme 2002–2004 (December 2001), accessed at http://bit.ly/1RxPvgY on 7 May 2015.

European Commission, European Political Strategy Centre, ‘In Defence of Europe. Defence Integration as a Response to Europe’s Strategic Moment’, EPSC Strategic Notes 4, 15 June 2015, accessed at http://bit.ly/1OzwpqI on 13 October 2013.

European Commission, Joint Statement by EU High Representative Catherine Ashton and Commissioner Štefan Füle on the Situation in Tunisia, Press Release, 18 January 2011, accessed at http://bit.ly/1JCkyYs on 26 August 2015.

European Commission, Multiannual Financial Framework 2014–2020 and EU Budget 2014, (2013), accessed at http://bit.ly/1LVgcbh on 27 October 2015.

European Commission, Towards an EU Response to Situations of Fragility—Engaging in Difficult Environments for Sustainable Development, Stability and Peace, COM (2007) 643 final (25 October 2015).

European External Action Service, European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument, Syrian Arab Republic, National Indicative Programme 2011–2013, accessed at http://bit.ly/1R2lsgv on 4 September 2015.

European External Action Service, Press Corner Website, accessed at http://bit.ly/1Zk3Wdt on 26 August 2015.

European Investment Bank, 2014 FEMIP Annual Report: Transforming Opportunities into Sustainable Impact (April 2015), accessed at http://bit.ly/1Mkl11N on 19 June 2015.

European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI), Revised National Indicative Programme (2011–2013) of the Syrian Arab Republic (2010), accessed at http://bit.ly/1R2lsgv on 7 May 2015.

European Parliament, Analysis of the National Indicative Programme (2011–2013) of the Syrian Arab Republic (22 January 2010).

European Union, Institute for Security Studies, Yearbook of European Security 2015, accessed at http://bit.ly/1IXNZ7t on 26 August 2015.

Eurostat, ‘File: First Time Asylum Applicants in the EU-28 by Citizenship, Q2 2014–2015.png’, Statistics Explained, updated 18 September 2015, accessed at http://bit.ly/1NEbhRH, on 5 November 2015.

Filiu, J.-P., Le Nouveau Moyen-Orient: Les peuples à l’heure de la révolution Syrienne (Paris: Fayard, 2013).

Friedman, T., ‘Obama on the World’, The New York Times, 8 August 2014, accessed at http://nyti.ms/1sGDBGx on 8 September 2015.

Fromkin, D., A Peace To End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East (New York: Holt, 1989).

Gallet, A., ‘Les Enjeux du Chaos Libyen’, Politique Etrangère, February 2015, accessed at http://bit.ly/1N2XOzy on 15 September 2015.

Hovland, K. M., ‘Norway Offers to Host Syria Donor Conference’, Wall Street Journal, 9 September 2015, accessed at http://on.wsj.com/1LLLGpw on 13 October 2015.

International Crisis Group, Flight of Icarus? The PYD’s Precarious Rise in Syria, Middle East Report No. 151, 8 May 2014, accessed at http://bit.ly/1VIVnV0 on 8 June 2015.

Portela, C., The EU’s Sanctions Against Syria: Conflict Management by Other Means. Egmont, Royal Institute for International Relations, Security Policy Brief No. 38, September 2012, accessed at http://bit.ly/1L3hEu0 on 26 August 2015.

Reuter, C., ‘The Terror Strategist: Secret Files Reveal the Structure of Islamic State’, Der Spiegel, 18 April 2015, accessed at http://bit.ly/1cGYWvz on 19 April 2015.

Spitz, R., State–Civil Society Relations in Syria: EU Good Governance Assistance in an Authoritarian State, Ph.D. dissertation, Universiteit Leiden (Leiden: LAP Lambert Academic Publishing, 2014), accessed at http://bit.ly/1L3lnaJ on 8 October 2015.Wikipedia, Syrian Civil War, Map of Syria’s ethno-religious composition in 1976, accessed at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Syrian_Civil_War#/media/File:Syria_Ethno-religious_composition..jpg on 9 November 2015.

Cover image: WMCES ownership.